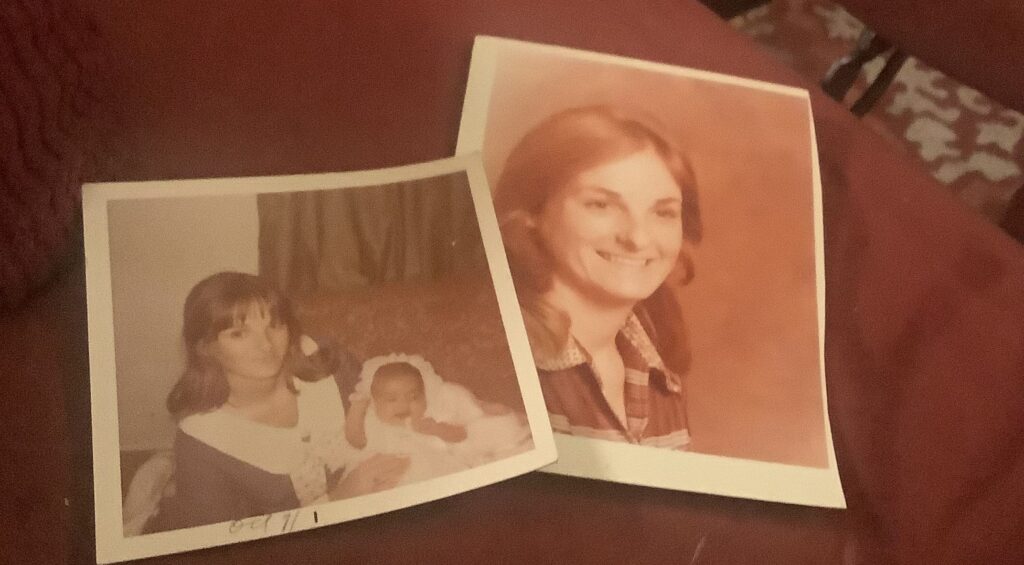

Susan McBrine is one of the four founding moms of the National Tuberous Sclerosis Association, Inc. (the original name of the TSC Alliance) along with Adrianne Cohen, Verna Morris and Debbie Castruita. Susan’s daughter Stacia was born in 1971 and was diagnosed at 9 months in the emergency room after suffering from infantile spasms. In 1974, Susan submitted a letter to Exceptional Parent magazine seeking out other families struggling to find information about TSC and she got 15 letters back in a week, three of which were from parents in Southern California. From their initial meeting came the idea to start an organization and from there the TSC Alliance was founded. Stacia passed away in 2003 when she was 32.

We had the opportunity to catch up with Susan to ask her about the early days of the organization, how things have changed over the last fifty years and what her hope is for the future.

Briefly describe your family’s journey with TSC. What were you told to expect for your daughter back then?

I was 23 when my daughter was born, she was my first child. When she was about nine months old, she started having infantile spasms, but I didn’t know what they were at the time. I took her to doctor after doctor and they kept telling me it was in my head and I was an overprotective mother. Finally, I took her to the emergency room when she had nine spasms in one day and she was seen by an ER doctor who had seen another TSC patient who was 12 years old, so he diagnosed her and told me that she would not walk or talk and she would die if her seizures weren’t controlled.

How did you translate your grief from the diagnosis into action?

After the diagnosis I went through the stages of grief and translated my frustration into doing my own research at libraries and I found out there hadn’t been research done on TSC in 100 years. I knew we needed to find more people to prompt more research. So I wrote a letter to Exceptional Parent magazine describing my daughter’s diagnosis and asked if there were any parents out there with the same diagnosis. I got 15 letters back in one week. One letter that lit a fire under me was from a mother who had a 29-year-old daughter with TSC and thought she’d never live to hear about another case. I contacted the three other mothers who wrote me from California and asked if we could meet and that’s where we started to think about forming an organization.

What did it mean to you to receive letters from other parents of children with TSC?

I think the real moving concept was it’s important to know we’re not alone. Getting those letters made me realize if we united, we weren’t ever going to be alone. We started out by writing a lot of letters and making a lot of telephone calls because there was no email and no internet at that time. I received a call from Marjorie Guthrie (one of the founders of the Committee to Combat Huntington’ s Disease) who similarly started with no money, just desperate parents and I’ll never forget her telling me she started with $5,000 and five parents, and research today has made all the difference for that disease as well.

What were the early days of the organization like? How did you organize and find other people in the 1970s?

We started a newsletter; we charged $10 per membership to cover the postage because we were getting so many letters and so many families interested. We started a physician advisory board and asked the doctors who were seeing our children to join as well as other pediatric neurologists. We found Manny Gomez, among others. Adrianne and I went to a conference hosted by the Child Neurology Foundation to talk to them. We were all in different stages of being parents and most of us had full time jobs also so the work we were doing was on a strictly voluntary basis. All of us contacted our local media. I was in the San Bernardino area and they did an article in our local paper about Stacia. We also contacted the regional centers for disability services in California and got the word out to the social workers. We also contacted all the institutions in the state and found parents that way. We got parents from different states and they spread the word in their states so it became an expanding network, which is still happening today. A friend of mine helped us file for nonprofit status and later Adrianne succeeded in getting us a grant for $50,000 and that was a turning point where we finally got some funding behind our efforts that kept us going and furthered our movement.

How did you connect with physicians?

For the most part we were reaching out to doctors already dealing with tuberous sclerosis. They didn’t really spend a lot of time, but they lent their name. I got my pediatric neurologist at Loma Linda to sign on as did others in the group. Then we found Manny Gomez, who had written a book about tuberous sclerosis, and who understood the significant burden parents face and the need for a support group. Everyone who has talked about him has said he had an incredible kindness and optimism. For parents who were being told not to expect much for their children, to have a doctor say “no, that’s not enough, you deserve more” made a huge difference. When my daughter had brain surgery at 13, the neurosurgeon had never dealt with a case of tuberous sclerosis before, so I handed him Manny’s book before he operated on her for eight hours.

Was there a moment or event where you felt like you had turned a corner and were starting to make real progress?

I think when we got that first grant and filed as a nonprofit organization, it gave is legitimacy. So when I went out to a regional center and talked to a group of social workers, I wasn’t just a mother talking about her kid. I was somebody that had an organization behind me. It’s just amazing to me that today, fifty years later, our organization is so stable and has an international outreach and has stable funding and research ongoing. I think we owe that to every single parent that took their grief and desperation when their child gets a tuberous sclerosis diagnosis and turns it into action and that’s what thousands of parents have done since we started it.

We had the opportunity to share your story as part of our 45th anniversary celebration. What do you consider to be the biggest changes in the last five years?

The most recent thing that I see that I’m excited about is the focus on the behavior issues in tuberous sclerosis because as bad as the seizures are and the all the physical manifestations, the behavior is the hardest for families to live with. I see it every day on Facebook, so to see to research focused on that is really exciting. The other thing is that parents are giving support to one another online and talking to each other and that’s making a difference nationwide and internationally. I’m excited that in my lifetime we got a genetic test and they are doing in utero diagnosis. So much has changed since my daughter was diagnosed. There was no MRI or cat scan, but now all that technology is making a difference in kids’ lives. Finally, it’s encouraging to see parents seek mental health services and therapy for themselves while dealing with the ongoing stress of tuberous sclerosis.

What is your biggest hope for the future?

My biggest hope for the future is there will be a TSC in every state because it is so hard for parents when they know there is a clinic that can help their child, but it’s a 10-hour drive or flight away. I also think we need to educate pediatricians and neurologists on how to treat TSC and talk to parents about this disease. This needs to be done starting at the college level and include raising awareness of infantile spasms so they don’t dismiss them and send people home. Finally, of course more research toward a cure would be nice. The fact that we have better medications and better treatments and better surgeries, it’s changed 100% for the better since the 1970s, but we still don’t have a cure.

How are you still helping support families with tuberous sclerosis complex and continuing the important work you started fifty years ago?

I try to stay active on Facebook and still try to connect parents with resources there. I also wrote a book for teachers of kids with severe disabilities because that’s what I do and it was about how teachers can more effectively deal with parents, so using my experience as both a Special Education teacher and parent. I think it’s important empower parents to be able to advocate for themselves. I try to walk a fine line because I think it depresses parents to hear that my daughter passed away from tuberous sclerosis, but I also think new parents don’t know the stages of grief and realize they are going through that. When we hear a diagnosis, we think of grief as something you deal with in death. But we grieve our lost dreams and what we had hoped for our child. A lot of parents don’t know its normal to have those feelings and to work through the process to acceptance of their new reality. That’s hard, so if I as a parent can help, I think I’ve done something positive. It takes parents supporting other parents to get through that, and just like it was at the start that still matters.

You’ve talked about how you had the privilege of seeing life through Stacia’s eyes, what were some of the enduring lessons that you carry with you today?

I got to see a total, unconditional love that never ends. It’s beautiful because she never really saw the ugliness in the world or the disappointments and failures. She was pretty happy most of the time. Seeing that unconditional love in her eyes and in the eyes of the students I taught was life-changing for me. I kind of feel sorry for people that that haven’t experienced that because it puts into perspective that money doesn’t matter, what you achieve doesn’t matter, all that really matters is loving people. Even when she was dying, I don’t think she understood what was happening, but to the day she died she was still smiling, still happy and still giving love. It was a spiritual experience for me and something I think about facing my own mortality.

Parents of children with tuberous sclerosis aren’t martyrs, we’re just doing the best we can because we didn’t have a choice. Dealing with this disease can be hell, it’s hard on marriages, it’s hard on siblings, but it also changes our perspective and teaches us to appreciate life no matter how hard it is.

You can learn more about Susan’s story from her guest post on the Mixed Up Mommy blog, from an interview in the Winter 2019 issue of Perspective Magazine and by watching her tell her story for our 45th anniversary Gala.